The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is a long-distance route that follows the path the Cherokee nation took during their forced relocation. The Cherokee Nation was removed from their lands in 1838 by the government of the United States.

TL;DR Don’t have time to read the full article? Here are my top finds:

🏨Hotels and Vacation Rentals

📍Tours

🐻 Save time! Buy your National Park Pass before your trip

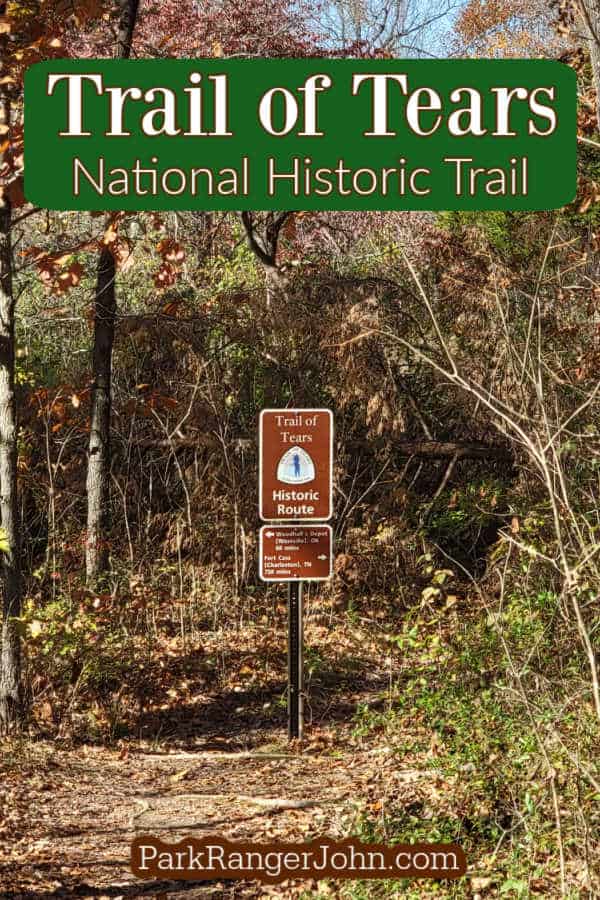

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

The National Historic Trail spans nine states, winding through North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Illinois, Missouri, Alabama, Kentucky, and Arkansas, ending in Oklahoma. Over 100,000 members of Native American tribes were made to leave their homelands. They were relocated to land the U.S government designated for them, called Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

The Native American tribes who inhabited the southeastern United States were ordered to relocate by the U.S government. The Indian Removal Act was passed in 1930, granting permission for Native Americans to be relocated to land in the west. What followed is a tale of despair, hopelessness, and death, but also perseverance.

Why Were Native Americans Forcibly Removed?

The Native American Tribes who lived in the southeastern United States had done so for generations. Their ancestors had hunted, lived, and died, on the millions of acres that spanned the states of Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina.

At the end of the 19th century, this vast area was occupied by white settlers who, with the help of the United States government, had forced the tribes to relocate. The Americans wanted the millions of acres occupied by the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles people to farm cotton.

The relationship between the people of the Native Nations and the Americans was tense. The relationship often devolved into violence, and as a result, neither side trusted the other.

The Americans slowly began pushing the Native Nations from their land as the demand for land and westward expansion grew. To try and keep the peace, and hopefully, some of their ancestral land, the Native Nations and the American government signed over 40 treaties. With each treaty, more Native land was given to the Americans.

Many state governments began to put pressure on the people of the native nations. In 1823 Native Americans could not legally own land.

State governments not only restricted Native rights but also burned their homes, murdered entire villages, and simply settled on land that belonged to the Cherokee.

In 1824, the Federal government offered the tribes land where they would be left alone by the American settlers in an attempt at voluntary peaceful relocation. Some tribes decided to relocate while others refused. The choice of voluntary relocation was abandoned when Andrew Jackson became the 7th President of the United States in 1828.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830

Andrew Jackson wanted to solve the ‘Indian problem’ once and for all. Jackson had fought in the Creek War in 1813 and believed in removing the Native Americans from their land. Jackson had been successful in helping the federal government drive the Seminoles and Creek nations from their land.

In 1830 Jackson implemented the Indian Removal Act. This Act gave the federal government the power to take land that belonged to the Native Nations who lived in the southern states east of the Mississippi. The Native tribes would be given land to the west of the river in Oklahoma.

The Indian Removal Act was the beginning of mass forced relocation. The removal of the tribes was supposed to be done without force and peacefully where possible. This was not the case, as many were treated with brutality. The forced removals began in the winter of 1831.

The Choctaw and Creek nations were the first to make the forced emigration from their ancestral land, on foot and sometimes in chains. The trek was arduous and incredibly long. 3,400 members of the Creek Nation died in Alabama due to the horrific conditions they encountered along what became known as the Trail of Tears.

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

The Trail of Tears is the collection of routes the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles people traveled to reach their new land in Oklahoma. The Trail of Tears commemorates the path that 17 groups of Cherokee, called detachments, traveled by land and water to reach the Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

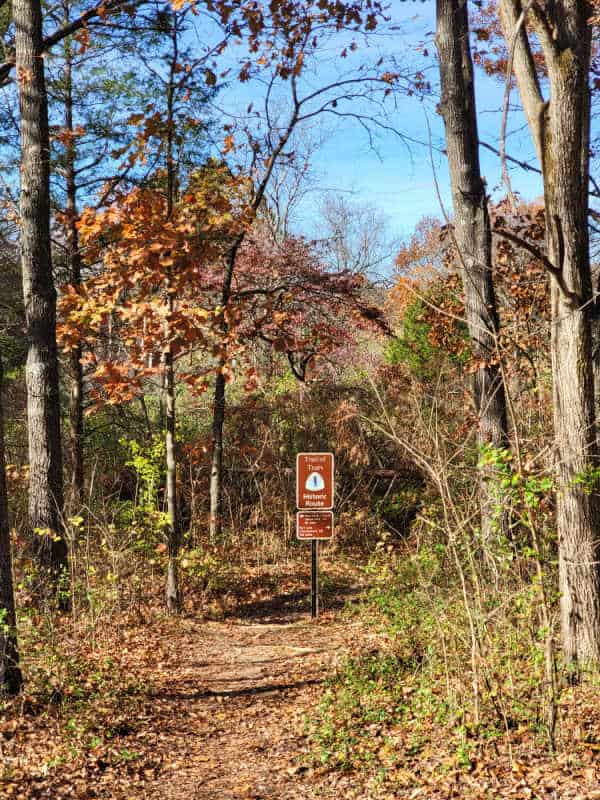

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail is comprised of places managed by the National Park Service and those that are managed separately. The sites that are managed separately have received NPS certification.

These parks tell the tale of the forced emigration of the Cherokee Nation from their home.

The National Parks Service has divided the trail into three trailheads beginning at the emigration depots. These are the forts the Cherokee were taken to after leaving the removal camps.

The emigration depots were at Fort Cass close to Charleston, Tennessee, Ross's Landing, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Fort Payne in Alabama.

Although the Trail of Tears was the historic route used by five Native Nations tribes, the National Parks Service focuses on telling the story of the Cherokee people’s forced emigration. The trail includes the many routes traveled, campsites, and the gravesites of those who died along the way.

The Cherokee and The Trail of Tears

The Cherokee people initially refused to comply with the Indian Removal Act. The Cherokee were considered by the Americans as being one of the five civilized tribes, as the Cherokee had adopted western culture. Some of the wealthiest Cherokee lived in sprawling plantations and were slave owners. The Cherokee was a thriving nation in the 1820s.

The pressure for the Cherokee to give large portions of their homeland to the U.S government did not disappear. When gold was discovered on Cherokee land, the U.S government was even more eager to resettle the Cherokee in the west.

Any rights the Cherokee had were stripped away. They were not allowed to own businesses, mine for gold, or testify against white people in court.

Not all Cherokee were against the government's offer of a land swap. A small group led by Major Ridge believed fighting the government was futile.

The government offered the Cherokee Nation 5 Million Dollars and land in Oklahoma in exchange for their ancestral homelands in the southeastern United States.

The group of Cherokee that followed Major Ridge signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1935, which agreed to the removal of the Cherokee. The twenty men who signed the treaty did not represent the entire Cherokee Nation. Many believed the treaty was passed illegally.

In 1838 the Cherokee were forcibly rounded up by the U.S Army and militia. They were forced to leave their homes in Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama. The old, young, and ill, were roundup at gunpoint. They were rounded up into removal camps and then sent to one of three emigration depots.

Routes on the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears consists of several routes; The Benge Route, The Bell Route, The Drane Route, the Northern Route, and the Water Route. The Cherokee began their journey west between August and November 1838.

Northern Route

This route was the route taken most often by the detachments. The Northern route was a land route that began in Southeastern Tennessee, through Nashville, and into Hopkinsville, Kentucky.

From Kentucky, the route passed through Anna, Illinois, Jackson, Missouri, through Springfield to the Missouri- Arkansas state line. Once in Arkansas, the Cherokee continued onto Fayetteville and then into Oklahoma.

The Water Route

The Water Route began in Southeastern Tennessee on the Hiwassee River from Fort Cass. The next stop was Blythe Ferry, where they joined the Tennessee River.

They traveled across the state to Ross’s Landing in Chattanooga, then into Alabama.

The Cherokee remained on the Tennessee River across Northern Alabama. From Alabama, the route took them across Kentucky to the Ohio River.

They followed the river to the Mississippi River and the border with Illinois. From Illinois, they traveled along the Arkansas River into Indian Territory.

The Benge Route

This land route began at Fort Payne, Alabama, where the group traveled to Memphis, Tennessee.

From Memphis, they made their way to Missouri, then into northeastern Arkansas. The route then continued to Fayetteville, where the group dispersed.

The Bell Route

This land route began at Fort Cass, Tennessee, with the first destination being Ross’s Landing. From there they traveled to Memphis. After Memphis, the groups crossed the Mississippi into Arkansas.

They traveled through Arkansas until they reached Evansville, where they disbanded into Indian Territory.

Alabama

Alabama is home to several sites where the Cherokee departed from the state for their journey westward. Many of the Cherokee leaving Alabama did so via waterways.

Lake Guntersville State Park, Guntersville

Lake Guntersville State Park preserves the site of the waterway used by several detachments of Cherokee. The State Park is the site of not only a water route but a land route too, known as the Benge Route after the Cherokee John Benge who led the detachment.

The detachments following the Benge Route began their journey at Fort Payne, crossed the Tennessee River at the State Park, and continued to Huntsville, Alabama.

The State Park was one of the water routes along the Tennessee River. The Tennessee River became Lake Guntersville when it was dammed.

Little River Canyon National Preserve, Fort Payne

Little River Canyon National Preserve was where in 1838, 1,100 members of the Cherokee, Muskogee, and Creek passed through.

The National Preserve houses a section of the Trail Of Tears where the detachment traveling with John Benge from Fort Payne crossed the Little River above the falls.

Russell Cave National Monument, Bridgeport

The Russell Cave National Monument served as a permanent shelter for the Native Nations tribes from around 10,000 BCE.

The cave now serves as a national monument to commemorate the forced removal of the Cherokee, whose ancestors made Russel Cave their home.

Tennessee

Tennessee is the ancestral home of the Cherokee people, and as such, housed 10 out of the 11 Indian Removal Camps. The Indian removal Camps were known for overcrowding and lacking necessities such as proper sanitation, food, and water.

Tennessee has several departure zones for the different trails the Cherokee would follow to reach Oklahoma.

The Tennessee River was the boundary between Cherokee Land and land that belonged to the United States. One of the largest deportation centers was in Tennessee at Fort Cass.

Brown's Ferry Tavern, Chattanooga

Browns Ferry Tavern is the home of the Cherokee leader John Brown. When the Indian Removal Act went into effect in 1830, Brown owned over 600 acres of Land in Chattanooga.

John Brown’s land was a boundary for Cherokee land and where many detachments of Cherokee walked past.

Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park - Moccasin Bend National Archaeological District

Located within the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, the Moccasin Bend National Archaeological District sheds light on 12,000 years of Native Nations occupation.

After 12,000 years of the Cherokee people living in the area now protected by the National Parks Service, they were removed between 1838 and 1839.

Some of the Cherokee living in the area were sent to Ross’s Landing. From there, they made their reluctant journey west.

Moccasin Bend was also a part of one of the water routes used by the Cherokee. The site includes the beginning of the Browns Ferry Federal Road Trace, a hiking trail that includes segments of original land traveled by the Cherokee.

Ross’s Landing, Chattanooga

Ross's Landing preserves one of the main departure points for the Cherokee. John Ross was a prominent businessman and Cherokee Principal Chief who operated a ferry service at what is now Ross’ Landing.

The site memorializes the brutal treatment of the Native Nations people who were forced to leave their homelands behind. In 1838 the site became a holding camp for the first three detachments of Cherokee to be forced to travel the Trail of Tears,

From Ross’ Landing, the detachments were taken to Waterloo Alabama, and then onto Indian Territory.

Stones River National Battlefield, Rutherford County

Before Stones River became a Civil War battlefield, the Nashville Pike served as one of the main routes for the removal of the Cherokee.

The Nashville Pike is protected by the National Parks Service not only as the site of a Civil War battle but also as a section of the Trail of Tears.

Natchez Trace National Parkway

The Natchez Trace National Parkway spans 444 miles and three states. The Parkway follows a historic travel corridor used by Native Americans for thousands of years. The historic corridor is known as the Old Natchez Trace.

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail crosses the Old Natchez Trace in several areas. Several different detachments used sections of the Old Natchez Trace as route segments.

Milepost 400.2 along the Natchez Trace marks the section where the 1092 people traveling along the Benge Route merged with the historic Natchez Trace.

Milepost 370 marks the point where the detachment of Cherokee following the Bell Route walked along the Natchez Trace.

Bells group had left Charleston by choice. The group of over 600 Cherokee in Bell's detachment supported the Treaty of New Echota.

Georgia

Georgia was one of the Cherokee homelands, and, as such, the state contains roundup routes. These routes were used to round up the Cherokee to place them in camps.

Running Waters - the John Ridge Home, Rome

John Ridge was a political figure within the Cherokee Nation. Ridge along with his father, Major Ridge, signed the Treaty of New Echota. John Ridge lived in the home known as Running Waters.

It was from this home that many have said ‘the Trail of Tears began.’

The group that would sign the Treaty of New Echota, which would become known as the Treaty Five, formed in the John Ridge Home. Many council meetings were held at the home.

It was during these meetings that the terms of the treaty were discussed. The last meeting of the Cherokee council in Georgia happened at Running Waters.

Vann Cherokee Cabin, Cave Spring

The Vann Cherokee Cabin was built in 1813 by a member of the Vann family, possibly Avery Vann, who was a member of the Cherokee Nation.

The cabin is situated in the Vann Valley, which is named after Avery Vann.

The site was hidden for years inside the Green Hotel, which was built around the site. Today the humble log cabin home serves as a place of reflection as a part of the Trail of Tears.

Cedartown Encampment/Removal Site, Cedartown

The Cedartown Encampment is the site of one of the removal camps where the Cherokee were interned before being moved to one of the deportation centers. The Removal Camps were notorious for their terrible conditions.

There was not enough space or resources for the number of people held there. The camps were rife with disease and death. Many Cherokee died in the camps before beginning their final journey.

North Carolina

In North Carolina, a group of Cherokee called the Oconaluftee Cherokee, were granted permission to remain in the western part of the state. This group did not live on Cherokee land and did not consider themselves as belonging to the Cherokee Nation.

The members of the Cherokee Nation from the east were rounded up and sent to removal camps. Some made the brave choice to try to escape the removal and hid in the mountains.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Close to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, there is a place called Cherokee. Here the Oconaluftee Cherokee managed to stay despite the Indian Removal Act.

When the Indian Removal Act was passed many Cherokee who lived in North Carolina fled and found safety in the Great Smoky Mountains.

The leader of this group was called Tsali. The U.S Army pursued the leader because he had killed several U.S soldiers.

The people who inhabited Cherokee at the foot of the mountains agreed to help the U.S track down Tsali.

Eventually, Tsali sacrificed himself to keep his people safe. Some of the people who had been hiding in the mountains with Tsali were allowed to settle in the town of Cherokee.

Kentucky

Parts of Kentucky once belonged to the Cherokee. Southwest Kentucky served as part of the route the Cherokee took to reach Illinois. The parks below preserve the story of the Cherokee as they continued their march through Kentucky.

Paducah Waterfront

The Paducah Waterfront is where four of the seventeen detachments of Cherokee passed through. One detachment traveling by water route led by Gustavus Drane stopped at the Paducah Waterfront to purchase supplies.

Trail of Tears Commemorative Park, Hopkinsville

The Trail of Tears Commemorative Park in Hopkinsville is the first non-federal Trail of Tears site to be included in the National Parks Historic Trail.

The park is the site of a campsite used by the Cherokee on their trek to their new home. The park is also home to a log cabin that dates to 1838.

The park protects the gravesites of two prominent members of the Cherokee Nation. Chief Whitepath and Fly Smith died while making the arduous journey west.

Mantle Rock Preserve, Livingston County

Mantle Rock Preserve was the site of a two-week-long winter encampment made by the Peter Hildebrand Detachment. The detachment was unable to continue because of the terrible and bitterly cold conditions.

The Hildebrand Detachment was not the only detachment to pass through the Mantle Rock area. Eleven of the seventeen detachments passed through the area during the harsh winter of 1838.

The winter was so harsh that the Ohio River had frozen in parts, making it impossible for the Cherokee detachments to cross. If the detachment did manage to cross the river, they became stranded between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

The Cherokee crossed the river into Golconda, Illinois by way of Berry’s Ferry.

The 60 Miles that the Cherokee traveled to cross the Ohio River into Illinois were the most deadly on the Trail of Tears.

Many Cherokee died while attempting to cross the Ohio River due to the extreme cold and lack of resources.

Illinois

The Cherokee journeyed through Kentucky into Illinois, where the Trail of Tears continues. Almost 9,000 Cherokee made their way through Illinois, following the Golconda-Cape Girardeau Trace.

Many Cherokee passing through Illinois were from the Great Smoky Mountain region in North Carolina.

The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail incorporates an auto-route of the path taken by the Cherokee in Illinois. The route begins at Cave-in-Rock, follows Route 146 north, and continues westward until it reaches the Mississippi River.

Illinois is home to several trail segments that are certified by the National Park Service.

These are the McGinnis Cemetery Trail Segment, in Anna, the Toler Farm Trail Segment six miles east of Anna, and the Wagner Farm Trail Segment, five miles west of Golconda. The last trail segment is the Jentel Farm Trail Segment, three miles outside Anna.

Wayside Store and Bridges Tavern Site, Johnson County

The Cherokee detachments passed through Johnson and passed by the Wayside Store and Bridges Tavern. The store and tavern were owned by John Bridges.

Many travelers stayed at the tavern, and the store provided the local community and travelers with provisions.

Eleven Cherokee detachments walked past the site, with oral histories claiming some Cherokee bought provisions from the Wayside Store.

Hamburg Hill, Union County

Hamburg Hill preserves 1,5 miles of the original trail that the Cherokee used. The trail winds down to the banks of the Mississippi River. From here, the Cherokee boarded ferries to take them across the Mississippi River and into Missouri.

Missouri

Thirteen detachments crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri during the Trail of Tears as they made their way through Missouri and into Arkansas.

Most detachments followed the Northern Route, which took them through Jackson, Missouri. Once through Jackson, the Cherokee made their way through Rolla.

The route then turned south-westward through Springfield and into Arkansas.

Trail of Tears State Park, Jackson

This State Park was created in memory of the Cherokee who died while attempting to cross the Mississippi River to enter Missouri. The park preserves the site where 9 of the 17 detachments crossed the Mississippi River during the winter of 1838 to 1839.

It was during this crossing that many of the Cherokee died due to hunger, exposure, and disease.

Henry E. Davis Homestead, Steelville

The homestead is an NPS Certified site, as are many of the sites featured along the Trail of Tears National Trail.

Thousands of Cherokee walked past the homestead on their forced march westward. The homestead appears as it would have in 1838 to 1839.

Arkansas

Hundreds of miles of the Trail of Tears passed through Arkansas. Each route traveled by the detachments passed through Arkansas as their lost stop before reaching Oklahoma.

Arkansas Post National Memorial Visitor Center, Gillett

The Arkansas Post National Memorial is a National Park site with a long history. The visitor center, in particular, features the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.

Arkansas Post served as an internment camp for those traveling along the water route in 1831 when the first detachments of Cherokee who agreed with the terms of the Treaty of New Etocha left voluntarily.

Fort Smith National Historic Site, Gillett

The Fort Smith National Historic Site preserves the history of the humans who have occupied the area for 12,000 years. Two Fort Smiths have been built on the site. Fort Smith served as the center of justice at the edge of the frontier.

The Fort Smith National Historic Site commemorates the hardships faced by the Cherokee during their forced removal at the Trail of Tears Overlook and River Walk.

The path overlooks the Arkansas River, where several detachments of Cherokee using the water route traveled up to reach Indian Territory.

At Fort Smith National Historic Site, you can stand where the weary Cherokee would have stood as they entered Indian Territory.

Pea Ridge National Military Park, Benton County

Before the Confederates and the Union fought the decisive Battle of Pea Ridge, the Cherokee marched through the area on the Trail of Tears. The park includes a three-mile section of the trail.

The trail segment is identified by a marker close to Elkhorn Tavern.

Between 1837 and 1839, 11,000 Cherokee walked through what is now part of the Pea Ridge National Military Park.

Oklahoma

Every route taken by the Cherokee, ended in the newly designated Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

In 1838 when the Cherokee began their forced march, there were 16,000 people on the trail. At the end of the six-month journey, hundreds of Cherokee had been buried on the route.

Many Cherokee died trying to reach Oklahoma. This was due to the horrendous conditions they experienced in the removal camps and on the Trail of Tears.

Thousands died once reaching Indian Territory as a result of the relocation. It is estimated that 4,000 Cherokee died during and after the Trail of Tears.

When the detachments reached Indian Territory, they were to proceed to their designated disbandment site. There were seven dispersal sites, of which the National Park Service has exhibitions at two.

One exhibit is at one of the most popular dispersal sites in Stilwell, called Ms. Webbers Plantation. Another exhibit can be found at George Woodall's Farm in Westville.

Upon arriving at the dispersal sites, the Cherokee were to be provided with provisions to start their new life.

The Cherokee were to be provided with supplies for one year after their arrival, as per the Treaty of New Echota. Sadly the Cherokee experienced further hardship due to a delay in receiving the provisions.

In 1841, the town of Tahlequah was made the capital of the Cherokee Nation. Despite the assurances made in the Treaty of New Echota that Indian Territory would remain untouched by American expansion, the Cherokee land was slowly taken by the U.S government.

The Treaty of New Echota preserved the Cherokee Nation, but at an extremely high cost. Today there are more than 400,000 members of the Cherokee Nation.

Additional Trail of Tears Resources

The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation (Book)

Step into Reading Trail of Tears (Kids Book)

A History from Beginning to End, Native American History (Book)

Trail of Tears Collection of 36 Documentary Films (DVD)

Additional National Park Resources

Oregon Trail National Historic Trail

California Trail National Historic Trail

Pony Express National Historic Trail

How many national parks are there in the US?

UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the US

Learn more about National Park Passes for parks that have an entrance fee.

$80.00 - For the America the Beautiful/National Park Pass. The pass covers entrance fees to all US National Park Sites and over 2,000 Federal Recreation Fee Sites for an entire year and covers everyone in the car for per-vehicle sites and up to 4 adults for per-person sites.

Buy your pass at this link, and REI will donate 10% of pass proceeds to the National Forest Foundation, National Park Foundation, and the U.S. Endowment for Forestry & Communities.

National Park Free Entrance Days -Mark your calendars with the free entrance days the National Park Service offers for US citizens and residents.

Make sure to follow Park Ranger John on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok

Leave a Reply